Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797–1851) was a prominent English novelist, short story writer, and dramatist best known for her novel Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus (1818), a groundbreaking work of Gothic Fiction and science fiction. She was the daughter of two radical thinkers: feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft (A Vindication of the Rights of Woman), and political philosopher William Godwin (a leading figure in the Enlightenment)

Tragically, her mother died shortly after her birth, leaving Mary to be raised by her father in an intellectually stimulating but emotionally complicated environment. At sixteen, she began a scandalous romance with the married Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, eventually eloping with him to Europe.

Their travels and association with Lord Byron led to the famous 1816 summer at Villa Diodati in Geneva, where the idea for Frankenstein emerged during a ghost-story competition. The novel, published when she was just twenty, became a literary sensation and remains a cornerstone of horror and speculative fiction.

Mary Shelley wrote other novels, including The Last Man(1826), Valperga(1823), Perkin Warbeck (1830), and Lodore (1835). Her short stories, such as The Mortal Immortal(1833), often explored themes of immortality, scientific ambition, and human suffering. After Percy Shelley died in 1822, she devoted herself to editing his works and supporting her son, but she continued writing until she died in 1851.

Mary Shelley’s legacy endures not only through Frankenstein but also through her contributions to Gothic literature, feminist thought, and early science fiction. Her works grapple with the ethical limits of human innovation, the consequences of playing God, and the isolation of those who defy societal norms and themes that remain profoundly relevant today.

Mary Shelley wrote several short stories exploring themes of immortality, science, and human suffering. The Mortal Immortal (1833) is one such tale, reflecting Shelley’s fascination with the limits of human life and the consequences of defying nature.

She was influenced by Gothic literature, which often dealt with supernatural elements, horror, and existential dread. Like Frankenstein, the story also reflects Romantic-Era concerns about the dangers of unchecked scientific ambition. It is written in first-person retrospective narrative.

Shelley experienced immense personal tragedy; her mother (Mary Wollstonecraft) died shortly after her birth, and she lost three of her four children early in life. These experiences shaped her preoccupation with death and immortality. The early 19th century saw rapid developments in medicine and chemistry, sparking debates about life extension, much like modern discussions on biotechnology.

The story subtly critiques societal expectations, as the protagonist, Winzy, suffers from immortality while his wife, Bertha, ages naturally, a possible metaphor for the constraints of marriage and gender roles.

It was published in 1833 in The Keepsake, a popular literary annual. Unlike Frankenstein, The Mortal Immortal was not widely discussed then but has since gained recognition as a precursor to modern speculative fiction. The story’s themes align with later works like Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890).

July 16, 1833.–This is a memorable anniversary for me; on it, I complete my three hundred and twenty-third year!

The story begins on July 16, 1833, on the three hundred and twenty-third birthday of the narrator, Winzy, the immortal man. He recounts the events that led him to drink an elixir when he was twenty, when he was a devoted apprentice to the famous Alchemist Cornelius Agrippa.

All the world has heard of Cornelius Agrippa. His memory is as immortal as his arts have made me.

Despite his humble status, Winzy is deeply in love with Bertha, an orphan raised by a wealthy old woman. She was his childhood friend and neighbor. Winzy was poor and was offered a job under Cornelius Agrippa. He used to do dangerous and supernatural experiments.

I cannot remember the hour when I did not love Bertha; we had been neighbors and playmates from infancy.

He represents the allure of forbidden knowledge and the potential consequences of tampering with nature. Winzy was confused, but he decided to work as an apprentice to Agrippa. His job was to deal with dangerous chemicals. As Agrippa started to make further advancements in his work, he consumed Winzy’s maximum time.

One day, Winzy cannot keep a date with Bertha, she becomes rude and vows to marry another man rather than Winzy, who could not be in two places at once for her sake. Jealousy begins to consume Winzy, but master Agrippa continues to focus all his efforts on a particular potion.

Though true of heart, she was somewhat of a coquette in manner, and I was jealous as Turk.

Bertha returns his affection, but she is pressured to marry a wealthier suitor. Desperate to prove himself worthy, Winzy seeks a way to secure his future. He drinks the elixir( a mysterious potion) meant to grant immortality, believing it to be a simple love charm. Though he initially doubts its effects, he soon realizes that he has stopped aging while those around him grow old.

He lives an endless life, watching his beloved aging and dying. At first, Winzy and Bertha enjoy happiness. He continues pursuing Bertha, and the two soon get married. As decades pass, Bertha ages while he remains youthful. Society grows suspicious, and Bertha becomes bitter and resentful. Winzy watches helplessly as his beloved withers away, while he continues living, unchanging.

Five years later, Agrippa got ill. On his deathbed, he called Winzy to confess that the elixir is not a cure for love but a potion made for immortality. It shook Winzy, who began to erode every facet of his life. He was not getting old, but his wife was getting older and finally died. Winzy was alone, and immortality became a curse for him.

A cure for love and for all things–the Elixir of Immortality. Ah! If now I might drink, I should live forever!

He saw everyone of his age dying. He wanted to escape. For this, he traveled the world and saw various nations dying. The whole world was changing, but he was stuck in a single state. He regretted and suffered a lot in his endless life. He desired to die and find peace.

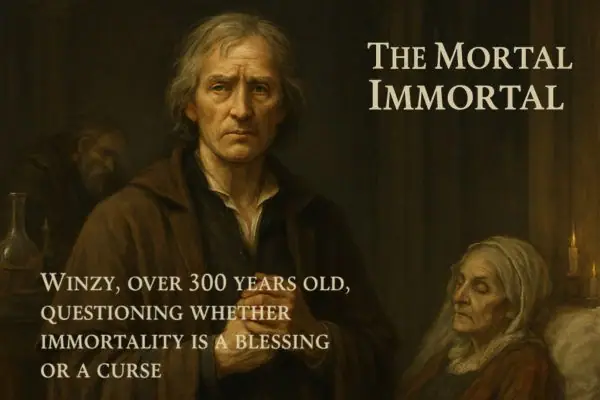

The story ends with Winzy, now over 300 years old, questioning whether immortality is a blessing or a curse, as he faces endless loneliness and the inevitability of outliving everyone he loves. Shelley’s tale serves as a cautionary reflection on the desire for eternal life, showing that immortality brings not fulfillment, but sorrow and isolation.

It raises important themes of human relationships, the paradox of scientific utility, obsession, and the limits of knowledge. Shelley concludes that immortality is a curse that radically changes human life. The main human features, according to the author, are mortality, the ability to love, and vanity.

Mary Shelley’s *The Mortal Immortal* (1833) is a Gothic short story that explores themes of immortality, love, and the human condition. The narrative is presented as the diary of Winzy, a man who inadvertently becomes immortal after drinking an elixir meant for his mentor. Below is an analysis of the main and minor characters in the story:

Winzy: The protagonist and narrator of the story. Initially, a young, poor student was in love with Bertha. He works as an assistant to Cornelius Agrippa, an alchemist. He accidentally drinks the elixir of immortality, believing it to be a cure for love. He embodies the suffering of immortality, showing how eternal life leads to isolation and despair.

As centuries pass, he remains youthful while watching Bertha and others age and die, leading to profound loneliness and regret. His immortality becomes a curse rather than a blessing, making him question whether he is truly immortal or just long-lived (mortal immortal).

Bertha: Winzy’s love interest and later his wife. She was a beautiful, orphaned girl raised by a wealthy old woman. A kind and affectionate but also somewhat vain and influenced by wealth, marries Winzy after he proves his devotion, but as she ages, she grows suspicious of his eternal youth.

Her jealousy and eventual decline into madness and death highlight the tragedy of immortality when one’s loved ones are mortal. represents the fleeting nature of human life and beauty, contrasting with Winzy’s unchanging state.

Cornelius Agrippa: The alchemist and Winzy’s mentor. Based on the real-life historical figure, Cornelius Agrippa is a Renaissance occultist. He seeks the elixir of immortality but fails to perfect it. His experiments led to Winzy’s accidental immortality. He represents the dangers of unchecked scientific and alchemical ambition. He symbolizes the dangers of pursuing godlike power through science and magic.

The Old Woman (Bertha’s Foster Mother): A wealthy woman who raises Bertha. Initially tries to persuade Bertha to marry a richer man than Winzy. She is a representation of societal pressures and materialistic values that contrast with Winzy’s sincere love.

Albert Hoffer: A rival for Bertha’s affection. He is a wealthier suitor preferred by Bertha’s foster mother. His presence creates tension in Winzy and Bertha’s relationship early in the story.

The Stranger at the Tavern: A man who listens to Winzy’s story in the framing narrative serves as the audience for Winzy’s confession. His reaction represents the horror and disbelief surrounding Winzy’s immortality.

Mary Shelley’s The Mortal Immortal (1833) is a short story that explores themes of immortality, love, and the burdens of eternal life. The protagonist, Winzy, recounts his tragic tale as he reflects on his unnaturally long life. He claims to be 323 years old at the outset of the story.

A sailor without rudder or compass, tossed on a stormy sea–a traveller lost on a wide-spread heath, without landmark or star to him- such have I been: more lost, more hopeless than either. A nearing ship, a gleam from some far cot, may save them, but I have no beacon..

One day, Cornelius Agrippa’s assistant, Albertus Magnus, attempts to steal a mysterious potion, an elixir of immortality from his master. Agrippa, furious, destroys most of it, but a small vial remains. Winzy, believing it to be a mere philtre(love potion), drinks it, hoping it will cure his lovesickness and make Bertha love him unconditionally.

At first, nothing seems to happen, and Winzy dismisses it as a failure. However, he soon notices strange changes; his body feels stronger, his mind sharper, and he no longer suffers from fatigue or illness.

Bertha, moved by Winzy’s devotion, marries him despite his poverty. For a time, they live happily, but as years pass, Winzy remains youthful while Bertha begins to age. Rumors spread that he has made a pact with the devil. Cornelius Agrippa, realizing what Winzy has done, warns him that the elixir grants eternal life but not eternal youth, meaning he will live forever but may still suffer the decay of age.

The power of exciting my hate -my utter scorn – my – oh, all but indifference!

The story explores the paradoxical nature of immortality, highlighting the loneliness and despair that can accompany eternal life. Winzy’s immortality becomes a curse rather than a blessing, as he is forced to endure the pain of loss and the burden of living while those around him perish.

Winzy’s decision to drink the elixir of immortality is motivated by his desire to be with Bertha forever. However, her death soon after leaves him consumed by guilt and regret, questioning the consequences of his actions and the value of eternal life without love and companionship.

As decades pass, Bertha grows old and resentful, accusing Winzy of witchcraft. She dies, leaving him alone. Winzy wanders the world, watching generations come and go. He fights in wars, learns countless skills, and even befriends historical figures, but his immortality becomes a curse.

By the time he narrates his story, Winzy is 323 years old, physically worn but unable to die. He questions whether Cornelius Agrippa’s other potion, the elixir of immortality, might reverse his condition, but he has lost track of it. The story ends with Winzy’s despairing realization that he may never find death, doomed to wander the earth forever, a prisoner of his immortality.

Winzy’s love for Bertha is destroyed by his inability to age with her, showing that even the strongest bonds cannot withstand unnatural existence. Like Frankenstein, this story warns against meddling with nature’s laws, as Agrippa’s alchemy brings only suffering. Winzy’s endless life drives him to near-madness, as he watches everyone he loves perish.

The Mortal Immortal is a haunting exploration of the human desire to conquer death. Shelley crafts a tragic tale in which immortality does not bring wisdom or joy but only endless grief. Winzy’s fate serves as a dark reminder that some boundaries between life and death, mortal and immortal, should never be crossed.

The Mortal Immortal is a story of regret and repentance. A man can not be immortal for his whole life, he has to die sooner or later. He remains human because of the finiteness of existence, life loses its sense without death.

Death! mysterious, ill-visaged friend of weak humanity! – Says Winzy.

Rhetorical exclamation and amplifying descriptive adjectives emphasize death as a blessed power. Without awareness of the finiteness of being, a person gradually loses moral character.

Yes, the fear of age and death often creeps coldly into my heart, and the more I live, the more I dread death, even while I abhor life. Such an enigma is man – born to perish –when he wars, as I do, against the established laws of his nature.

This comparison underlines the unreasonableness of humans’ struggle with the inevitable. The main character is dual: he is not immortal, but he is also not mortal.

The inextinguishable power of life in my frame, and the ephemeral existence…– sadly notes Winzy at the end of the narrative.

The reception of the opposition emphasizes the duality: the strength of life and ephemeral existence. Winzy does not live, he is waiting for death that will not come. Mortality makes human beings human since life can be appreciated only after realizing its finiteness. Guided by naive love, he falls into the trap of his immortality:

With quick steps and a light heart.

Shelley uses parallelism to underline the self-irony of Winzy, who looks at himself 300 years ago. Love for Winzy at the beginning of the story is a destructive force. The author emphasizes the strength of the memory, using a rhetorical exclamation. Winzy bitterly sneers at his desire to be cured of love.

Sad cure! Solitary and joyless remedy for evils which seem blessings to the memory

A strong metaphor highlights the change in perception: the remedy for evil becomes the blessing of memory. After Bertha’s death, there is less of a human in Winzy; he reflects on high matters and remembers his youth with a bitter smile. Love is what makes people human because, having lost the ability to love, a person becomes a soulless shell.

People are naturally vain, care about the outside, and look for third-party approval. The immortal has more reasons to consider himself better than others, which is manifested in his personality. The author’s irony reveals the true thoughts of Winzy: he understands his vices and does not hide them. Vanity pushes Winzy to drink the unknown alchemist’s elixir.

A bright flash darted before my eyes

This technique of shifting the perception point emphasizes the impulsiveness of an act, dictated by a vain desire to get rid of human affection. Throughout the story, it becomes obvious that Winzy enjoys his youth. He is rather embarrassed by Bertha’s aging.

Dark-haired girl and jealous old woman are his expressions that describe her. The author’s technique of contrast emphasizes the internal changes of the main character and his wife. Over the years, Bertha becomes an earthly woman, desiring a normal life. Winzy, on the contrary, renounces earthly living and refuses conceited thoughts.

With age, Winzy moves away from vanity, gradually ceasing to be a human. Mortality, the ability to love, and vanity are integral parts of human nature. Mortality allows a person to realize the value of life. Having lost the ability to love, a person ceases to be a human.

Vanity manifests itself in every person, unleashing the narcissistic part of personality and concern for the external; a person loses touch with earthly life. Using the themes of mortality, love, and vanity, Mary Shelley in The Mortal Immortal states that immortality is a curse that goes against human nature and violates the value of life.

Situational Irony: Winzy drinks the elixir thinking it will cure his love for Bertha, but instead, it makes him immortal, forcing him to watch her grow old and die. Cornelius Agrippa seeks immortality but fails, while Winzy gains it accidentally.

Dramatic Irony: The reader understands the **horror of immortality** long before Winzy fully grasps it.

The Elixir of Immortality represents human ambition and the danger of defying natural limits. Bertha’s Aging & Death symbolize the inevitability of mortality and the pain of eternal life. The Diary represents memory, time, and the burden of endless existence.

Dark, Melancholic Tone: The story is filled with despair, decay, and psychological torment.

Supernatural & Uncanny: The elixir grants unnatural life, creating a **Gothic horror** of endless existence.

Isolation & Madness: Winzy’s immortality leads to loneliness, while Bertha descends into jealousy-fueled insanity.

References to Cornelius Agrippa: A real-life occult philosopher, adding historical weight to the story.

Biblical & Mythological Undertones: The quest for immortality echoes the Fall of Man (Adam’s expulsion from Eden) and Greek myths(Tithonus, who aged eternally without dying).

The title itself, The Mortal Immortal, is a paradox, capturing Winzy’s tragic state: he is physically immortal but emotionally mortal, suffering as humans do. Winzy’s existence becomes a living contradiction; he cannot die, yet he is not truly alive.

Visual & Sensory Imagery: The fading youth of Bertha vs. Winzy’s unchanging appearance.

The crumbling elixir bottle symbolizes the fragility of life.

Time Imagery: References to centuries passing, seasons changing, and the relentless march of time emphasize Winzy’s curse.

Shelley evokes pity and sorrow for Winzy’s plight, making his immortality a tragedy rather than a blessing. Bertha’s decline and death heighten the emotional devastation of the story.

Winzy frequently questions his existence: Am I then immortal? Why should I live, when all I love must die? These emphasize his existential despair and helplessness.

How does Shelley explore the theme of immortality in the story?

Answer:

In The Mortal Immortal, Mary Shelley turns the concept of immortality into a haunting exploration of suffering rather than triumph. Unlike traditional tales where eternal life is a reward, Shelley presents it as a cruel joke, one that robs existence of its purpose and joy. Winzy, the protagonist, stumbles into immortality by drinking an alchemist’s potion, believing it will secure his future.

Instead, he finds himself trapped in a nightmare where time stretches endlessly before him, barren of meaning. As he watches his beloved Bertha wither with age while he remains unchanged, he laments, I am a monster, a blot upon the earth—a spectre. His agony deepens as he realizes that immortality does not spare him from grief, loneliness, or the slow erosion of his humanity.

Shelley’s story strips away any romanticism surrounding eternal life, exposing it as a form of living decay. Winzy’s existence becomes a paradox—he cannot die, yet he is no longer truly alive. The more time passes, the more he resembles a ghost among the living, detached from the natural rhythms of life.

His despair reaches its peak when he cries, Is this what it means to be immortal? To watch the world crumble while I remain, unchanging and unwanted? This question lingers over the narrative, emphasizing Shelley’s warning: immortality is not an escape from death but a surrender to something far worse—an eternity of emptiness.

Through Winzy’s torment, Shelley criticizes humanity’s reckless pursuit of defying natural limits, much like in Frankenstein. The elixir, like Victor’s experiments, is a product of arrogance, and its consequences are irreversible. Society shuns Winzy, not out of fear, but because his unnatural state disrupts the order of life and death.

ultimately, he is left with nothing but the hollow realization that mortality, with all its brevity and sorrow, is preferable to an endless existence stripped of love, hope, and rest. Shelley’s message is clear: the true horror is not death, but being denied it.

What does the story suggest about the human desire for eternal life?

Answer:

The story presents a haunting critique of the human desire for eternal life, revealing it not as a triumph but as a profound curse. Through the tragic experience of Winzy, who accidentally drinks an elixir of immortality, Shelley explores the devastating consequences of escaping death.

At first, Winzy believes the potion will bring him happiness, perhaps even securing the love of Bertha, but he soon realizes his terrible mistake.

I am, in fact, a mere mortal who, by accident or fate, has become entangled in the meshes of eternity.

His words capture the cruel irony of his existence, neither fully immortal nor able to die, he is trapped in a nightmarish in-between state. The greatest torment of Winzy’s endless life is watching those he loves wither and die while he remains unchanged. His wife, Bertha, grows old before his eyes, her beauty fading while he stays young.

Bertha grew old; she was fifty years of age, and I still twenty. She was wrinkled and toothless; her once raven hair was white, her eyes dim, while I retained the freshness of youth.

This painful contrast strips away any illusion that eternal life is desirable; instead, it makes love a source of agony rather than comfort. Shelley suggests that the very impermanence of life is what makes love meaningful; without death, human connections become unbearable.

As centuries pass, Winzy’s immortality isolates him completely. He becomes a ghost among the living, forced to flee whenever people notice his unnatural youth. I am an outcast from the world; I have no country, no friends, no home, he laments.

His existence is one of endless loneliness, mirroring the fate of other Gothic figures who defy natural laws, much like Frankenstein’s creature, who is also rejected by humanity. Shelley underscores that immortality does not elevate a person but instead cuts them off from the very things that make life worth living.

By the story’s end, Winzy does not cherish his endless years but despairs of them, longing for release. His final cry Is it not better to die than to live a death-in-life?—a corpse with a beating heart? reveals the true horror of his condition.

He is not alive in any meaningful sense but merely exists, a shell of a man burdened by endless time. Shelley’s message is clear: the desire for eternal life is a delusion, a defiance of nature that leads only to suffering.

I am a blot upon the earth; a monster, whom all men fear and hate, Winzy declares, echoing the fate of those who seek to transcend human limits. The Mortal Immortal serves as a warning that death is not the enemy but the necessary counterpart to life, and without it, existence becomes a curse.

How does Shelley critique the pursuit of scientific knowledge without ethical considerations?

Answer:

Mary Shelley’s story is a pursuit of scientific knowledge, demonstrating how unbridled ambition divorced from ethical considerations leads to ruin. Winzy’s tragic fate stems from his blind consumption of an alchemical elixir, mirroring the dangers Shelley had earlier explored in Frankenstein.

I had drunk of the elixir of eternal life; and I was doomed to exist forever, dragging out a miserable and hopeless existence, Winzy laments, revealing how scientific (or in this case, alchemical) breakthroughs, when pursued without wisdom, become curses rather than blessings.

The elixir’s creator, Cornelius Agrippa, serves as another cautionary figure, an intellectual so consumed by his experiments that he fails to recognize their horrific potential until it’s too late. Shelley particularly condemns the arrogance behind such pursuits through Winzy’s gradual realization of his mistake.

Unlike traditional Gothic villains who are punished for obvious sins, Winzy’s transgression is more subtle, the sin of thoughtless curiosity, of reaching for godlike powers without considering whether mortals should wield them. His eventual state mirrors Victor Frankenstein’s creation, suggesting that both scientific and alchemical overreach produce similar isolation and despair.

Shelley’s critique extends beyond alchemy to all forms of knowledge pursued without a moral compass. Winzy’s endless life becomes a prison precisely because no thought was given to what immortality truly means for a human soul.

The story’s power lies in transforming what might initially seem like a blessing, eternal youth into the worst possible fate, proving that knowledge without wisdom is humanity’s most dangerous temptation. Through Winzy’s suffering, Shelley argues that the true measure of progress isn’t what we can achieve, but whether we should achieve it at all.

Is Winzy truly immortal, or is his immortality an illusion?

Mary Shelley deliberately blurs the line between true immortality and cursed longevity inThe Mortal Immortal leaving Winzy’s condition hauntingly ambiguous. While he believes himself doomed to eternal life, declaring I am, in fact, a mere mortal, who, by accident or fate, has become entangled in the meshes of eternity.

There are suggestions his immortality may be a prolonged, decaying existence rather than true invulnerability. The elixir grants him extended youth but not necessarily indestructibility, as evidenced by his growing despair and physical deterioration of spirit: *”I retained the freshness of youth, though my soul grew aged and weary.

This paradoxical state where his body resists time while his mind crumbles that reveals Shelley’s clever subversion of immortality tropes. Winzy himself questions the nature of his condition, wondering Was I indeed immortal, or was this but the protracted youth preceding sudden decay?

This existential doubt permeates the narrative, suggesting his immortality might be a cruel trick of prolonged vitality rather than genuine eternal life. The story’s title itself, The Mortal Immortal, reflects this fundamental contradiction, positioning Winzy as neither fully alive nor dead, but suspended in a torturous middle ground.

His lament that I drag on this death-in-life existence implies he’s become less immortal and more undying, a distinction that makes his fate all the more terrible. Shelley thus crafts a version of immortality far more psychologically devastating than simple eternal life, a curse of half-existence where the protagonist outlives everything meaningful while never gaining the godlike permanence he might have imagined.

How does the story portray love and relationships in the face of immortality?

Answer:

It presents love as the ultimate casualty of immortality, transforming what begins as romantic devotion into a slow-motion tragedy. When Winzy first gains eternal youth, he naively believes it will secure Bertha’s affection: I shall always be young, and always beloved he muses. But this illusion shatters as time warps their relationship into something grotesque.

The cruel irony emerges in their physical contrast: *”Bertha grew old; she was fifty years of age, and I still twenty. She was wrinkled and toothless. Shelley strips away any pretense that love could survive such imbalance, revealing how immortality perverts the natural synchrony of human bonds.

The story exposes the particular agony of watching love decay while being powerless to stop it. Winzy’s torment comes not from abandonment but from painful constancy: *”She loved me still, but it was with a jealous, exacting love that grew peevish with time.”

Even Bertha’s dying words carry this poisoned intimacy: Husband…you have been young so long! an accusation masquerading as endearment. Shelley reserves her most devastating insight for Winzy’s existence after Bertha’s death, when immortality reveals its true emotional cost.

Without his mortal anchor, he becomes a wanderer upon the earth, friendless and alone, condemned to watch subsequent relationships crumble through repetition. Where Romantic poets might frame eternal love as transcendent, Shelley renders it as cyclical trauma, not a grand passion but a recurring wound.

The story’s final irony lies in Winzy realizing too late that mortality was love’s necessary counterpart: The elixir had preserved my youth, but at what cost? I had outlived every tenderness. In Shelley’s ruthless calculus, immortality doesn’t elevate love; it makes a genuine connection impossible, leaving only its hollowed-out shell.

How does Shelley’s treatment of immortality differ from other Gothic or Romantic writers?

Answer:

Mary Shelley’s immortality treatment in The Mortal Immortal stands apart from her Gothic and Romantic contemporaries through its psychological realism and rejection of transcendental idealism. While Romantic poets like Keats and Byron often aestheticized eternal life, as in Keats’ Bright star! Would I were steadfast as thou art”* with its yearning for love beyond mortality.

Shelley presents immortality as a decaying reality. Her approach contrasts sharply with the metaphysical grandeur of Wordsworth’s intimations of Immortality, where childhood memories suggest a divine pre-existence. Shelley’s Winzy experiences no such spiritual transcendence, only the crushing weight of endless days.

Compared to Gothic writers like Matthew Lewis in The Monk, who treat immortality as a supernatural spectacle, Shelley grounds Winzy’s suffering in disturbingly human terms. Where Lewis’s immortal characters face dramatic divine punishments, Shelley’s horror lies in quiet accumulation: Bertha grew old; she was fifty years of age, and I still twenty.

This domestic tragedy feels more terrifying precisely because it lacks theatrical damnation, the real horror is time’s uneven passage between lovers. Even Bram Stoker’s Dracula, written decades later, romanticizes immortality through vampiric seduction, while Shelley denies Winzy any such dark glamour.

Most strikingly, Shelley diverges from her husband Percy’s Romantic visions of eternal renewal in Prometheus Unbound. Where Percy’s immortals transcend human limits, Mary’s Winzy embodies their cruel paradox.

His question of immortality epitomizes her unique contribution, transforming immortality from a philosophical abstraction into a psychological prison, making The Mortal Immortal not just a Gothic tale but a pioneering work of existential horror. Unlike Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, who finds redemption through suffering, Winzy’s curse offers no catharsis, only Shelley’s devastating insight.

Alas! I had drunk of the elixir of eternal life, and I was doomed to exist forever. Her immortality isn’t mythic, but human – and therefore all the more unbearable.